The world of coffee is increasingly hit by the unprecedented negative impact of global COOLING, a phenomenon which since 2007 and for at least another 5-10 years still to come is expected to continue to cause havoc to coffee crops in producing origins across the world. Surprisingly to many, such weather events are NOT new and were actually first described in this article published all the way back in 2012 by SpillingTheBeans’ owner and Chief Analyst Maja Wallengren. Global Cooling also helps explain why coffee production in Brazil ahead of the new 2023 harvest for the 3rd crop year in a row is seeing both arabica and conilon regions being hammered with everything from the most damaging frosts in 40-50 years to the most severe drought in 90-100 years, and everything in between from monster hailstorms, flooding, extreme cold weather and hurricane-force winds. And all at the same time. This article was first published by the Melbourne-based Global Coffee Review in the Nov/Dec 2012 edition. Read on to understand how Global Cooling is affecting coffee production today, why the evidence points to a cycle of cooling for the next 10 years to continue and what the impact is for the industry.

By Maja Wallengren

Nov. 23, 2012 (GCR Magazine)–When anti-globalisation activists in 1999 ravaged Starbucks coffee shops in what became known as ‘The Battle of Seattle’, a lot of the talk centered on the effects of global warming. Former Vice President Al Gore would go on to win an Oscar for his documentary on climate change, as scientific and political debates have continued to focus on global warming. But some scientists are now pointing out that since 2007, the world has gradually moved into a phase of global cooling. After around 30 years of warmer weather, the world is most likely set to see the effects of La Niña, a period of cooling, for the next 20 to 25 years that will replace the highly talked-about El Niño.

“The climate on Earth has constantly been changing for over 4.6 billion years and the formation of mountains and volcanic activity continues to create new weather cycles,” says Alvaro Jaramillo, a leading scientist who has spent his career studying the effects of climate on coffee at The National Coffee Research Centre (Cenicafé). “We have to try to start improving our understanding of how El Niño and La Niña actually work, and how this is affecting the global climate at large,” Jaramillo recently told a packed audience at the annual coffee congress in Guatemala. For over 100 years, scientists and climatologists have observed that global weather patterns shift from warmer to cooler cycles every 25 to 30 years, based on ocean currents in the Pacific Decadal Oscillation and other weather patterns. Jaramillo argued that the direct link between greenhouse emissions and global warming has not been well represented in the public debate, with the interaction of natural warmer and cooler cycles largely ignored. While Jaramillo says that greenhouse gasses likely boosted warming effects, he argues that the warmer weather was from 1977 until 2006 partially the result of natural weather cycles. This change followed a prolonged period from 1947 to 1976 when the earth saw cooler weather.

“Since 2007, what we have seen is that the world is actually entering a new era of global cooling in which we, for the next 20 to 25 years, will see weather patterns dominated by La Niña rather than El Niño,” he tells Global Coffee Review. The result of this latest change in global weather helps explains why Colombian coffee producers have suffered four consecutive crop failures since 2008. With La Niña producing significantly cooler weather, higher rainfall and a “dramatic reduction” in sun exposure to coffee farms, the weather has by far been the main culprit behind Colombia’s harvest troubles, says Jaramillo. “In Colombia we have seen six years with relentless rains and very little sun exposure, which in the specific case of coffee has resulted in a massive drop in productivity. In order to have a good flowering develop into a good crop, coffee trees need an average of 4.8 hours of sun exposure every day. But in this period we have seen the average sun exposure reduced by over 30 per cent to between 3 and 3.5 hours a day. With the reduction in sun exposure it’s impossible to produce the same yields as seen before 2007,” says Jaramillo.

Like it or not, this new weather trend is expected to dominate the global coffee climate for the next 20 years at least, he says, something producers will need to take into account when planning ahead. Farmers will need to start selecting varieties more resistant to these weather effects in their renovation and replanting efforts. “There is no doubt that climate change is having a dramatic effect on coffee and we will still see a lot more of that coming in the next few years, even if nobody really knows for sure what will happen and why,” says Jack Scoville, Vice President at The Price Futures Group in Chicago.

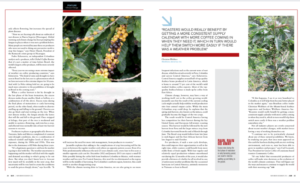

While the cause of climate change continues to be a point of contention within both the scientific and political worlds, its existence is being less contested. Coffee producers have seen plenty of first hand evidence of La Niña making its mark in the coffee lands. Producers from East Africa to South-East Asia have good reasons to continue to be concerned. For the last five years, the coffee world has witnessed an onslaught of weather-induced problems affecting crops. Four years of crop failure in Colombia; unseasonal drought followed by excessive rains in Brazil; five tropical storms including two hurricanes in Mexico and Central America in October 2011; drought in East Africa; and erratic monsoons in South-East Asia. Unpredictable weather not only affects flowering, but increases the spread of plant diseases.

“Now we are hearing talk about an outbreak of rust disease in Nueva Segovia [Nicaragua]. Global warming and climate change has been prompting this fungus in places where it was not a problem before. Many people are worried because these are producers who were not used to doing any preventive work to stop this fungus,” says Henry Hueck, President of the Ramacafe estate group in Nicaragua.

Pedro Echavarria, an independent Colombian analyst and a producer, tells Global Coffee Review that it’s just a matter of time before Brazil, the world’s largest coffee producer, will be more severely affected. “Every year we are seeing a more extreme impact of weather on coffee producing countries,” says Echavarria. “The kind of rains and drought we have seen in Brazil in the last year is a phenomenon which we have not seen to this extreme degree for 18 years. And with La Niña taking hold we are going to be much more attentive to the possibilities of both frosts and also drought in Brazil in the coming years.”

When a coffee harvest is hit by drought in the last phase of the bean formation, the excess dryness makes beans smaller, black or hollow, or a combination of all the above. Excess rains during the final phase of maturation or early harvesting period, on the other hand, often results in cherries swelling up and falling to the ground. Cherries can also go black and start rotting on the tree. When rust disease strikes, the fungus attacks the leaves that will die and fall to the ground. Once stripped of foliage, that part of the tree is weakened and unable to sustain a flowering, and even less a crop, and affected trees normally take at least two harvest seasons to recover.

Producers in places as geographically diverse as Tanzania, India and Mexico complained of constant semi-drought conditions, due to a combination of reduced rainfall and higher levels of direct sun-exposure, during the 1980s and 1990s. This was due to the dominance of El Niño during these years.

“It’s a legitimate question to ask how the market is going to deal with this. The weather uncertainty is happening and the market will deal with the supply and demand according to what’s going to be out there. But when you don’t know how to forecast how much will be available in the next crop, that uncertainty will be very hard to create the conditions to send the prices sharply down,” says Scoville. “It will increase the need for more risk management, from producers to roasters.”

Jaramillo explains that adding to the complications of crop forecasting will be the years in between the regular weather cycle where an opposite pattern occurs. Even if La Niña predominantly influences the next 25-year climate cycle, every four to five years a smaller opposite cycle can hit. December 2012 and January 2013 can expect a small El Niño possibly hitting the coffee belt from Southern Colombia to Mexico, with warmer weather and less rain. For Central America, this won’t be too detrimental as the region will be in the middle of harvesting. For Colombia’s southern region, however, this could result in another disappointing crop. “With the climate turning drier in Latin America, we are also going to see more frequent infections such as the current wave of rust disease, which has struck severely in Peru, Colombia and across Central America,” says Echavarria.

Central America supplies around half of top-quality Arabica beans produced in Latin America, which is home to around 75 per cent of the world’s mild washed Arabica coffee exports. Most of the top-quality Arabica balance is made up by coffee from East Africa. Climate change, however, may have a way of working itself out in the coffee growing world. Jaramillo says that the result of the current cooling cycle might actually help stabilise world production into four annual output cycles. While the main Colombian crop could drop, he explains that the spring mid-harvest, also known as the mitaca, could gradually become the bigger of the two crops. The result would be Central America having less competition for their harvest during the key United States and European fall-winter roasting season. This harvest would be followed by the new harvest from Peru and the larger mitaca crop from Colombia harvested from the end of March through June. The Brazil crop would follow from late June to mid-August and the East African harvest from late August to mid-October. For producers, if such a new cycle develops, this could improve their opportunities to sell at the right time, while roasters could benefit from more stable flows of fresh supply. With four regular and relatively equal production volumes smoothened out during the 12 months of the year, it would also provide a bit more of a buffer for all involved in case of unforeseen weather problems like the occasional hurricane in Central America, untimely monsoons in Vietnam or frost in Brazil.

“If this happens, I see it as very beneficial to Colombia as it will help them become better placed in the market again,” says Brazilian coffee trader Christian Wolthers of the Miami-based Arabica importers and brokers Wolthers America Inc. “Roasters would really benefit by getting a more consistent supply calendar with more coffee coming in when they need it, which in turn would help them switch more easily if there was a weather problem somewhere else.”

Not all industry players are overly concerned about recent weather changes, with market forces having a way of working themselves out.

“I continue not to be particularly alarmed about any of these natural possibilities. We know, by studying our past, that since man appeared on this earth he has been dealing with an ever evolving environment, and even so, man has been able to grow in numbers and prosper,” says Carl Leonard, Vice President for Green Coffee of Louisiana-based roasters Community Coffee. “It’s my belief that resourceful producers of coffee will make wise decisions as the evolution of the world’s climate continues. They will figure out the ways and means to continue to supply the world with their morning cup.”

See more coffee news and analysis pieces on: https://www.gcrmag.com/the-effects-of-global-cooling-on-the-coffee-cycle/

-0-

My name is Maja and I’m a Danish born woman crazy beyond passionate about everything coffee. I have written about all aspects of coffee for over 25 years from 60 coffee producing countries across the world.

My name is Maja and I’m a Danish born woman crazy beyond passionate about everything coffee. I have written about all aspects of coffee for over 25 years from 60 coffee producing countries across the world.

We, appreciate Your Letter and Thank You for Writing it .

Cordially ,

Arthur Siegfried Guth-Zapata

⚜️

.